If it is OK with you, I would like to spend some time this evening talking about why the landmark case of United States v. Windsor which I argued before the United States Supreme Court in 2013 is such a quintessentially Jewish case. The Windsor decision led to a rapid and dramatic change in moral understanding about the equal dignity of gay men and lesbians, change that took place on at least three levels–the level of the individual, change within our community and change in the law.

Perhaps the dominant view in our culture today is that religion, or belief in God, is inimical to the concept of change. That, after all, is the sense one gets when the media talks about evangelical Christians – that they preach a vision of life and law that cannot tolerate any deviation from the explicit Biblical text. The same, of course, is true within Judaism as well. Not only do certain groups of ultra Orthodox Jews hold a similar theory about Jewish law, or halakhah, but some even refuse to tolerate change in even the most mundane circumstances – for example, by refusing to use the internet or by insisting on wearing a particular type of fur hat in today’s Jerusalem that their ancestors wore in 17th century Ukraine.

The very idea that I, as a woman, not to mention a married lesbian mom, am standing on this bimah talking to you right now would be utterly inconceivable to them. Indeed, there can be little doubt that at least some of what is motivating the most vehement Trump supporters today is the sense that too much change has happened too fast, that changes in the civil rights of African-Americans, women or LGBT people created more harm than good, that we need Donald Trump to “make America great again.”

But what I hope to be able to demonstrate to you today is that this kind of stubborn refusal to accept, welcome or adapt to change is not the only way to be religious or to believe in God. And it certainly is not the only or even the proper, interpretation of our tradition. Inherent in Jewish belief is the view that people, communities and even the law must and should change when times and ethical circumstances demand it.

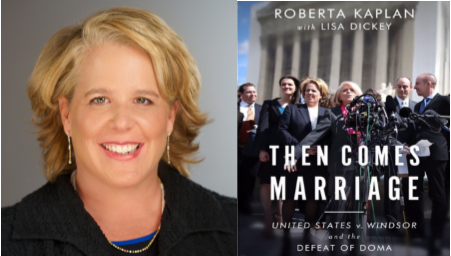

Let me start at the level of the individual. In the context of the Windsor case itself, there is no questions that most if not all of the key players in the case were themselves Jewish, including myself. My wife Rachel Lavine and I were married in a traditional Jewish ceremony in 2005. Our son Jacob Philip Kaplan-Lavine not only can probably never avoid being identified as a Jew given his name Jacob Philip Kaplan-Lavine, but, at the ripe old age of 10, is adamant that he want to be a rabbi when he grows up.

My client Edie Windsor not only grew up in a middle class Jewish family in West Philly, but married another Jewish woman, Thea Spyer, whose family had left Amsterdam to escape the Holocaust. A lot of people joked after we won Windsor that it had to be the first if not only Supreme Court case handled almost entirely by a bunch of Jewish lesbians.

Indeed, because so many of us were Jewish, many of the key turning points in the case were marked by the Jewish calendar. I, for example, felt like the nerdy law geek version of Sandy Koufax when the Second Circuit scheduled oral argument on the day after Yom Kippur. This meant that rather than spend the day before the argument furiously studying the case law, I spent it in synagogue with Edie and my family instead. I have to admit, however, that practically as soon as I had managed to take a bite of bagel and lox after sundown, I retreated to my office to go through my outline for at least the 752nd time.

In fact, my 2013 argument before the Supreme Court happened only a couple of days after the first night of Passover. So even though I was already well ensconced in a Washington D.C. hotel room by that time, my wonderful wife Rachel organized a seder at our hotel attended by more than two dozen people, including Edie, Pam, most of the lawyers on our team, my parents Richard and Bess Kaplan, Rachel’s mother, brother and sister and their families and even the Israeli parents of the then girlfriend of Jacob’s beloved nanny who happened to be in town that day. As you can imagine given the momentousness of what was about to take place, that was a seder that none of us will ever forget. Indeed, even though the hotel was the Mandarin Oriental, Rachel somehow managed to make sure that we were served matzoh ball, rather than won ton soup.

It was the change that Edie Windsor experienced in her own lifetime from meeting Thea Spyer in 1963 and falling in love with her, to living so many years in the closet, to becoming engaged to Thea in 1967, to ultimately getting married and coming out to everyone they knew in 2007 that led to our victory. Indeed, throughout the case, I kept a yellow post-it note on my laptop computer that read ‘”It’s all about Edie, stupid.” In other words, from the very beginning, we believed that we ultimately would win our case if we could convince the judges and justices that the marriage that Edie had with Thea, despite all the bigotry and homophobia, was really no different than their own marriages. On this point, we surely succeeded. As Justice Kennedy wrote in his opinion, the law that we struck down known as the Defense of Marriage Act or DOMA instructed “all federal officials, and indeed all persons with whom same-sex couples interact, including their own children, that their marriage is less worthy than the marriages of others. The federal statute is invalid, for no legitimate purpose overcomes the purpose and effect to disparage and to injure those whom the State, by its marriage laws sought to protect in personhood and dignity.”

Moving from the individual to the community, the same is true for the understanding of LGBT people within Judaism itself. The Jewish Theological Seminary, for the first time in its entire history, submitted an amicus brief in a court case. Which case, one might ask? United States v. Windsor, when JTS, along with the entire Conservative movement, joined an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to strike down DOMA as unconstitutional. Think about that for a moment if you will – only 10 years ago, any gay person who wanted to be ordained as a rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary had no choice but to be in the closet. But in 2013 in Windsor, and again in 2015 in Obergefell, JTS signed on to a brief submitted to the United States Supreme Court arguing that the marriages of gay people should be respected under the law.

And I certainly don’t have to tell you that we have seen the same kind of change in our nation as well. When we filed our case in 2009, New York did not permit gay couples to marry. That’s why Edie and Thea, like Rachel and myself, had to go to Toronto to get married. In 2011, New York passed its own marriage statute, making it only the sixth state to grant gay people the freedom to marry. When I argued the Windsor case before the Supreme Court, 9 states permitted gay couples to marry. By the eve of the Obergefell decision in 2015, thanks in large part to Windsor itself, 37 states already permitted gay couples to marry.

Last year, according to a NBC/WSJ poll, 58% of Americans say that they supported the legalization of same-sex marriage nationwide. The current level of support is more than double the 27% in Gallup’s initial measurement on gay marriage in 1996, when DOMA was first enacted based on the view, as expressed by the House of Representatives, that they wanted to show “moral disapproval” of gay people. Even president-elect Trump, in an interview with Leslie Stahl on 60 Minutes, said that as far as he was concerned, the question of marriage equality was “settled.”

But where the proverbial rubber hits the road is change in the law. The question of whether and to what extent Jewish law can change is the central debate that divides religious Jews today and in the past.

This same dynamic, but this time in the context of American constitutional law, was at play in my now famous exchange with Chief Justice John Roberts during the oral argument in the Windsor case. That exchange involved a debate about what really has been driving the dramatic transformation in American attitudes about gay people. The Chief Justice suggested that Americans were following the lead of elected officials. He asked me the following: “I suppose the sea change has a lot to do with the political . . . effectiveness of people . . . supporting your side of the case?” I responded by explaining my view that the change was instead one of ethical perception, the result of a changed “understanding that there is no . . . fundamental difference that could justify . . . categorical discrimination between gay couples and straight couples.”

But the Chief Justice then pushed further, noting that “as far as I can tell, political figures are falling over themselves to endorse your side of the case.” My answer then and my answer today is the same — what truly has driven the change is not the so-called political power of gay people, but instead the opposite of the moral disapproval expressed by Congress in 1996, “a moral understanding” that gay people are no different, and that their relationships are no from the relationships of straight couples.

Let me move on now to another law I am challenging in federal court, this time a law in Mississippi known as HB 1523.

On June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that because gay and lesbian Americans are endowed with “the fundamental right to marry,” the Constitution does not permit states to “exclude same-sex couples from civil marriage on the same terms and conditions as opposite-sex couples.” Obergefell, 135 S. Ct. at 2604–05. The reaction to Obergefell by some in Mississippi was stark. On the very day of the Obergefell decision, for example, Speaker of the Mississippi House Philip Gunn declared that “[t]his decision is in direct conflict with God’s design for marriage as set forth in the Bible . . . I pledge to protect the rights of Christian citizens[.]” Geoff Pender, Lawmaker: State could stop marriage licenses altogether, The Clarion-Ledger (June 26, 2015, 4:47 PM), http://www.clarionledger.com/story/politicalledger/2015

/06/26/bryant-gay-marriage/29327433/.[1] Several months later, in February 2016, Speaker Gunn introduced HB 1523 in the Mississippi legislature. ROA.16-60478.764.

At the heart of HB 1523 is Section 2, which designates the following three religious beliefs or moral convictions that entitle their holders to exclusive legal benefits: (1) “Marriage is or should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman;” (2) “[s]exual relations are properly reserved to a marriage between one man and one woman;” and (3) male and female “refer to an individual’s immutable biological sex as objectively determined by anatomy and genetics at the time of birth.” HB 1523 § 2 (together, the “Section 2 Beliefs”). HB 1523 animates the State’s preference for those religious beliefs by providing that the “state government” (defined broadly to include state actors as well as private citizens seeking to enforce a right under state or local law) shall not take any “discriminatory action . . . wholly or partially on the basis” that a person acts in a wide array of contexts “based upon or in a manner consistent with” a Section 2 Belief. Id. §§ 3, 4, 9(2).

HB 1523 is a far cry from the “exceedingly limited” statute depicted by Appellants. (Br. at 8.) Section 3(5), for example, does not merely allow “private citizens” to “decline to participate in same-sex marriage ceremonies,” as Appellants suggest. (Br. at 6.) Instead, it permits individuals and for-profit corporations to refuse to provide a virtually unlimited array of “marriage-related services, accommodations, facilities, or goods” including but not limited to jewelry sales and car-service rentals for a purpose related to the “solemnization, formation, celebration, or recognition” of any marriage. HB 1523 §§ 3(5), 9(3) (emphasis added). Thus, a restaurant manager in Jackson, Mississippi who chooses not to “recognize” the marriage of a lesbian couple, for example, is empowered by Section 3(5) to refuse to seat them together at a table for two on their anniversary, despite Jackson’s ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Jackson, Miss. Code of Ordinances §§ 86-301–306. Appellants’ contention that HB 1523 “does not authorize any business to discriminate” in “access to places of public accommodation” (Br. at 8) is simply false.

Likewise, Section 3(3) does not merely allow adoptive and foster parents to “raise their children in accordance with” their beliefs (Br. at 6–7), it prohibits the state from intervening to protect the best interests of gay or transgender children in the care of adults who may hold one or more of the Section 2 Beliefs. Id. §§ 2(a), 2(b), 3(3), 8(3); Miss. Code. Ann. §§ 43-15-13, 93-17-11. For example, if a foster parent were to subject a gay or lesbian foster child to corporal punishment or confined isolation for “disobeying” one of the Section 2 Beliefs, the State would be powerless to protect that child.

Similarly, Section 3(4) does not only allow “private citizens” to refuse to provide counseling and psychological treatment on the basis of a Section 2 Belief in clear violation of professional ethical guidelines—it also permits state employees, including public school guidance counselors, to turn away students who need care. Id. §§ 3(4), 9(3)(a). This provision of HB 1523 is arguably the most alarming since it would allow a school psychologist or guidance counselor to cease therapy with a depressed, suicidal high school student who divulges to the counselor that he thinks he might be gay.

Similarly, Section 3(7) of HB 1523 does not merely protect state employees who “express a [Section 2] belief”—it prohibits supervisors from taking any action whatsoever to attempt to resolve workplace conflict so long as one state employee claims to have been speaking “based upon or in a manner consistent with” a Section 2 Belief. Br. at 7; HB 1523 §§ 3(7), 4(1) (expansively defining “discriminatory action” to include any form of discipline and any material alteration to the terms or conditions of a person’s employment).

Contrary to Appellants’ assertion (Br. at 7–9, 30), Section 3(8) of HB 1523 does not impose any practical limitation on the right to recuse oneself from granting marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples. HB 1523 § 3(8)(a). Although the statute purports to require a clerk seeking recusal to “take all necessary steps” to ensure that the issuance of marriage licenses is not impeded or delayed, it provides no enforcement mechanism, imposes no penalty or consequence for failure to take such steps, and does not appropriate any funds that may be necessary to hire a new clerk in an office where all the clerks have recused themselves. Id.; ROA.16-60478.755 (identifying ambiguities in Section 3(8)(a)).

Perhaps even more surprisingly, Section 2 incorporates the religious belief that straight couples should not have pre-marital sex as a basis for refusing to provide wedding licenses, psychological counseling, or other goods and services. HB 1523 §§ 3(4), 3(5), 3(8). Not only does this obviously have nothing to do with “protect[ing]” the religious liberty of “opponents of same-sex marriage,” (Br. at 6), but this means that HB 1523 could arguably be applied to a large number of Mississippians: According to recent statistics compiled by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 90% of Americans have sex before marriage. CDC, National Survey of Family Growth (July 28, 2015), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/key_statistics/p.htm. Thus, pursuant to HB 1523, a jewelry store clerk could refuse to sell a diamond ring to a newly-engaged straight couple if he believed that the couple had previously had sex. HB 1523 §§ 2(b), 3(5)(b).

Finally, HB 1523 authorizes individuals or entities who discriminate in the name of any of the Section 2 Beliefs to obtain an injunction against any private party’s effort to obtain relief under anti-discrimination law or via the tort system. HB 1523 §§ 4, 5, 6. And not only that—the statute grants holders of the Section 2 Beliefs a private right of action to seek monetary damages from the State or from victims of their discrimination who try to seek administrative or judicial relief. Id. §§ 6, 9(2)(d) (defining “state government” to include “[a]ny private party or third party suing under or enforcing” a state or municipal law). A prospective plaintiff trying to bring an as-applied challenge to HB 1523 in the future, as Appellants propose (Br. at 37), could thus be sued under HB 1523 for bringing such a lawsuit, could be enjoined, and even ordered to pay damages as a result.

HB 1523’s other legislative sponsors were also very clear about the law’s sectarian basis. For example, State Representative Dan Eubanks, a co-sponsor of HB 1523, dramatically declared that HB 1523 “protect[s] . . . what I am willing to die for [and what] I hope you that claim to be Christians are willing to die for and that is your beliefs.” Id. at 16-60478.1786:18–20. This statement is similar to one made by Defendant Governor Bryant concerning HB 1523: “[I]f it takes crucifixion, we will stand in line before abandoning our faith and our belief in our Lord and savior, Jesus Christ.” Emily Wagster Pettus, Mississippi governor: ‘Secular’ world angry at LGBT law, The Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Miss.) (June 1, 2016, 9:48 AM), http://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/politics/2016/05/31/

mississippi-governor-secular-world-angry-over-lgbt-law/85208312/.[2]

Rabbi Jeremy Simons testified that none of the three religious beliefs in HB 1523 are held within Reform Judaism, which is the denomination to which most Jews in Mississippi belong. Id. at 16-60478.1172:14–17, 16-60478.1184:1–11. Rabbi Simons further explained the impact of HB 1523 on him as follows: “On the one hand, it makes me feel very upset that my religion is seen as somehow less legitimate because I cannot identify with the so-called sincerely held religious beliefs. On the other hand, it makes me very angry because I consider myself a religious person with deeply held religious beliefs. And by God, if someone were to hear me say this and assume that I believe anything that is in this statute, that is a tragedy that I have to explain that this is not me and this is not my religion.” Id. at 16-60478.1185:25–1186:8.

That is the kind of change, the kind of tikkun olam, or repair of the world, that lies at the heart of our tradition. It is, I believe, what God commands of every individual, every community, even of the law, even of God.

So what do we do now in these dark and scary times? I, for one, refuse to give in to inertia or despair. Martin Luther King famously once said that “the arc or the moral universe is long, but bends toward justice.” Significantly, Dr. King did not use the metaphor of a straight line. Like an arc, as in the Torah, the concept of tikkun olam ebbs and flows. The great Hasidic rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, who also lived in scary times and who suffered from depression his whole life, said that “All the world is a very narrow bridge, and the most important thing is not to be overwhelmed by fear.”

I also think it’s worth remembering the words of Edie Windsor three years ago on the steps of the Supreme Court after oral argument in our case when she was asked to explain why such dramatic change in the legal and societal acceptance of gay people had taken place. Edie explained that: “I think what happened is at some point somebody came out and said ‘I’m gay.’ And this gave other people the guts to do it.” Amazingly, Rabbi Heschel said almost the exact same thing years before: “All it takes is one person… and another… and another… and another… to start a movement.”

[1] As the District Court observed, the statements of Mississippi officials in response to Obergefell are reminiscent of statements made more than sixty years ago after the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). ROA.16-60478.762–763. See also Carolyn Renee Dupont, Mississippi Praying: Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement, 1945–1970, at 7 (2013) (“In twenty-first century America, evangelicals have widely come to accept that their Gospel includes a mandate for racial equality. Yet this . . . causes them to forget that their rather immediate forbearers served as serious obstacles to the aspirations of black Americans because they regarded this very principle as profoundly unchristian.” (emphasis in original)).

[2] At the preliminary injunction hearing below, Rev. Hrostowski testified in response as follows: “[W]hen [Governor Bryant] says, Christians will line up to be crucified for this, that is . . . in my mind blasphemy. Jesus was crucified as an atonement for human sin, not so that we could oppress one another.” ROA.16-60478.1208:10–13.